The presence of Buddhism in North America in the early 1950s was largely the result of Asian immigration, although there was growing interest in Zen Buddhism among the so-called “Beat Generation.” For the first six years that Reoch and his parents attended the Toronto Buddhist Church they were the only non-Japanese there. They first took part in its Sunday services in 1954 after meeting its spiritual director the Rev. Takashi Tsuji.

The central practice of the Jodo Shinshu sect is reciting the “nembutsu”, calling on the name of Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Compassion. Few books on Buddhism were available in those years in local bookshops; the family ordered what they could from overseas, many from the Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy, Sri Lanka. After the death of his father in 1966 and prior to leaving Toronto for London, Reoch and his mother attended Soto Zen meditation courses at the Rochester Zen Centre, USA, and York University, Canada.

During his years of work for Amnesty International in Asia, he continued his private Buddhist practice without belonging to any organization. His work brought him into contact with the Tibetan community in exile and, while in India, he secured intervention by His Holiness the Dalai Lama on behalf of Buddhist monks imprisoned in the Republic of Viet Nam (South Viet Nam).

Shambhala

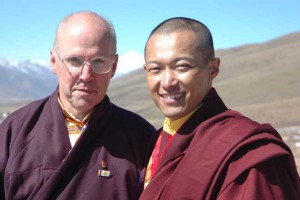

After 23 years of working for Amnesty International, he entered the training offered by the Shambhala community started in the West by Tibetan meditation master Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In 1994, Reoch received the Buddhist name Tashi Changchup, Auspicious Enlightenment, from the son and heir of Chögyam Trungpa: The Sakyong, Jamgön Mipham Rinpoche – revered as the rebirth of Mipham the Great, said to be a living embodiment of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom.

Among the many short films he made for the Shambhala community, this multilingual presentation, “Countless points of light”, shows the global reach of the Shambhala teachings. It includes an illumination of the Shambhala emblem, The Great Eastern Sun, created from hundreds of lighted candles.

After attending a three-month Shambhala seminary in 1996, he received transmission into the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism, and was appointed Director and Chair of the Council of the London Shambhala Meditation Centre. From 1999 to 2001, he directed the planning of the Consecration of The Great Stupa of Dharmakaya at Shambhala Mountain Center in the Colorado Rockies, USA – an international gathering of 1,500 people at 6,000 feet in the mountains.

A year later, Reoch was appointed by Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche to the position of President of the worldwide Shambhala organization, a position he held from 2002 until 2015, travelling worldwide to many of its more than 200 centres and groups, teaching and leading retreats. He now serves as the Personal Envoy of the Sakyong of Shambhala.

During his period as President of Shambhala, he toured with Buddhist Nun Ani Pema Chödrön, co-leading events on the theme “Practicing Peace in Times of War” and taught widely on the life and legacy of the Indian Emperor Ashoka, famed for renouncing war.

Compassionate Abiding Practice

As part of the “Practicing Peace in Times of War” tour, Ani Pema Chödrön introduced participants to the practice of Compassionate Abiding. It is a profound method of working with intense emotion, based on the classical text, The Way of the Bodhisattva, by the great master Shantideva.

Reoch was later asked by Shambhala Mountain Center to offer this practice as a filmed guided meditation for its Awake in the World online program.

The film includes an explanation of the practice and its application as well as a real-time session for live practice.

In May 2015, he was among a group of some 200 Buddhist leaders, from all different schools, who were invited to the White House in Washington DC for a meeting with key staff in the Obama administration. Delegates signed the Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change and later, a statement following the massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

A Buddhist Brawl

Mindful Politics – A Buddhist Guide to Making the World a Better Place was published by Shambhala Publications in 2006. The editor, Melvin McLeod, wrote: “Around the world, long-standing wars are driven by the terrible cycle of revenge, of wrongs committed in response to previous wrongs. Elsewhere, conflict and alienation are fueled by fear, insecurity, jealousy, hatred and greed. And everywhere, people are divided from their fellow human beings by the fundamental dualistic split between self and other, the split that Buddhism says is the root of all our suffering.” The publication includes the following article, “A Buddhist Brawl”, by Richard Reoch.

Not so long ago a brawl broke out in a Buddhist shrine room. A close friend of mine was involved. The retreat leader was injured and needed treatment. It all happened in a very lovely retreat centre near where I live.

They were having a weekend devoted to non-violence, and had invited a guest facilitator to lead the retreat. He wasn’t a Buddhist, but knew about group dynamics.

On the second day, the retreat leader proposed a role play. Two of the participants would be “kidnapped” by a terrorist group. The rest would have to negotiate for their freedom.

The retreat leader was to play the terrorist with whom they would negotiate. He opened a pack of cigarettes, took out a match and lit up.

“Excuse me,” said one of the participants, “there’s no smoking in the shrine room.”

The leader paid no attention. He smoked on in silence.

“Please put out the cigarette. We don’t smoke in the shrine room.”

“I don’t give a damn about your smoking rules,” said the terrorist coldly. “Do you want to talk about smoking, or do you want your friends back?”

“We won’t negotiate with you until you respect our shrine room,” said someone who was emerging as a leader for their side.

“OK,” said the terrorist, “I’ll stop.” He stood up slowly, sauntered over to the shrine, took a last puff and stubbed out his cigarette in the lap of the buddha.

Gasps filled the room. This was no longer play acting. People rushed up to see if the buddha rupa had been damaged.

“What do you think you’re doing?” someone shouted. “That’s a buddha!”

“I don’t give a damn. It’s not my buddha. This is not my shrine room. I’ve stopped smoking. Do you want to talk about your friends or shall I leave?”

People were irate. Events were overtaking them. No one wanted to talk about the hostages; they were obsessed with the assault on the buddha.

One person went up to the retreat leader and talked to him straight from the heart. “We invited you here to lead this weekend. We know this isn’t your community or your tradition. But this is our sacred space. All we ask is that you honour that.”

“Would you like to see how much I respect your space?” he replied. He walked over to the corner and pissed on the floor.

The whole room lunged forward. The first person to reach him knocked him to the ground. The rest joined in, shouting, beating and kicking him as he curled up on the floor to protect himself from the blows.

Eventually he managed to drag himself out of the shrine room, told the two “hostages” to rejoin their fellow practitioners and abandoned the weekend.

Friends, this is the way these events were told to me. In these dark and turbulent times, I often find it helpful to remember them.