A daughter of the Buddha on the

frontlines of war

“Victory over war!” they screamed. They formed armies, flew flags, infiltrated each others’ forces with spies, and laid the legions of their enemies low – all under the watchful gaze of one of the greatest Buddhist masters to flee Tibet and teach meditation in the west.

Their teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, chose mountain valleys and secluded woodlands for their mock battles, skilfully configuring them to bring a rising generation of teenagers face to face with their own hatred, fear and aggression. He was training them, not to fight wars, but to wage peace.

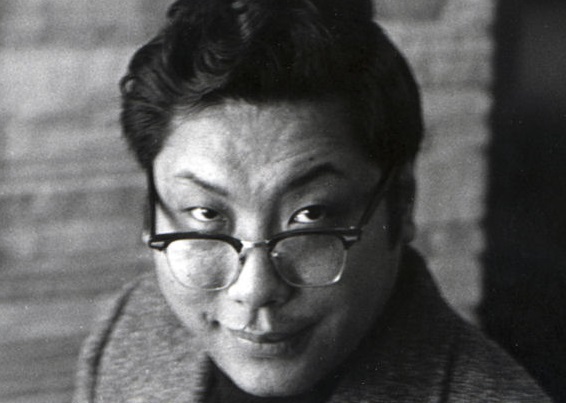

Among his recruits was Kiri Westby, a young woman born into a remarkable family in Boulder, Colorado. Now, thirty years on, armed with her unconventional early training and having served on the frontlines of world efforts for peace and human rights, she has written a startling first book: Fortune Favors the Brave: An Extraordinary Memoir.

The book opens with a Chinese interrogator spitting and yelling in her face just after she has been seized for unfurling a “Free Tibet” banner at Mount Everest base camp. It’s Olympic year in China and the protest captures the attention of the global media.

As the military officer she calls “Scary Fat Man” pounds his fist on the table and she starts sweating, she drops “almost unwillinging” into meditation and begins to recall her training in the mountains many years earlier.

She recalls the moment when the opposing youth “armies”, with comrades “captured “or “killed” in the skirmish as they threw flour-bags at each other, came face to face.

“We would stop a few feet away,” she writes, “lock eyes with our rivals and recognize that the others are actually us, defending their territory with the same passion and intensity, two sides of the very same coin. We were then taught to model true bravery by making a different choice at that crucial moment; to drop our weapons first, recognize our shared humanity, see our similarities over our differences, and bow to one another instead of fighting further.”

“It was an exercise in holding one’s mind steady in the midst of extreme chaos and confusion,” she says, “of overriding the instinct to destroy or be destroyed; of outsmarting the pitfalls that had plagued humanity for millennia.”

Sacred warriorship

This training in “sacred warriorship”, as Trungpa Rinpoche called it, may have been the application of ancient wisdom, but it was also prophetic. Kiri was being trained just as the tsunami of hatred, divisiveness, and harm that is currently sweeping across the globe was gathering force. Today we witness what is happening in country after country, affecting countless people, spawning vast humanitarian crises and threatening the progress humanity has made towards international cooperation, peacemaking and the protection of fundamental human rights.

She first had a sense of what her training had prepared her for when, at the age of eighteen, her parents enabled her to visit South East Asia and, with a friend, she slipped across the border into the ongoing civil war with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, hoping to visit the ancient Buddhist temples of Angkor. Noticing a fenced-in camp by the side of the road at a truck stop, she went closer to take a look. It was a refugee camp run by the International Red Cross. She could only catch a glimpse of what was inside, but it brought home to her the reality of the Cambodian genocide, its “killing fields” and ensuing war.

“I see men and women working inside the camp,” she recalls, “doing something useful to help the displaced, responding to the needs of innocent victims and I long to be inside. This is no childish game in the woods. This is real-life war, suffering on a massive scale, and I desperately want in. What I do know, in that very instant, is that there is a role for me to play in this suffering world, the camp is clear evidence of that, and I finally know – without a doubt – what I want to be when I grow up.”

The Buddha’s legacy

It is puzzling when people say that “engaged Buddhism” is a western invention. Even now people complain that social justice has been “imported” into the dharma. I recommend they read Fortune Favors the Brave. It is a living answer to those who question whether the Buddha’s teachings can be practiced in the midst of profound social engagement.

The idea of Buddhists working for the betterment of society, and to alleviate suffering, and is neither western nor new.

When I was little, my family joined a Japanese Buddhist community. At the end of every service we chanted the aspiration to “follow in the footsteps of the Buddha and dedicate our lives to the welfare of all humanity.” I took those words literally and ended up devoting my life’s work to peace, human rights and the environment.

That work has taken me often to Asia, which has given me an opportunity to study more fully the legacy of the Buddha’s life. Born in a time of war, he witnessed many horrors, including the devastation of his own homeland, the Kingdom of the Sakyas. His people fell prey to a conquering invader who is said to have “washed his throne with the blood of the Sakyas.”

So tormented was the Buddha by the aggression that engulfed the world of his time that it led him to take one of the most radical personal, social and political stances in the history of human endeavour.

He repudiated the entrenched structural injustice of his day, rejecting the entire caste system and establishing his own classless communities wherever he went. The early followers of the Buddha were contemplative social radicals. They didn’t seek to own anything. They ate only what others offered them and whatever they received they shared as a community. They shaved their heads and wore robes so that, as they approached in the distance, it was virtually impossible to distinguish one from another and certainly not a male from a female. That was the idea. They were working on a new social experiment that would manifest, not their differences, but their common humanity.

As they walked through the towns and villages of the North Gangetic plain, they were throwing off the shackles of social privilege, gender oppression and the entire economic model of their day.

They knew exactly what they were challenging. They put their lives on the line, yet they carried no weapons. In fact, there is a story of an Indian King who comes to beg the Buddha not to accept the droves of young men who were coming every day to be his followers, because it was placing the very existence of his armed forces at risk.

Transformative power

These are the footsteps in which Kiri Westby has walked. She has worked to combat the oppression of women, starting with a program in Nepal to expose and prevent the trafficking of young women into brothels, and later calling out institutionalized racism in the fellowship that funded her research project. Kiri was an intern at the UN headquarters during the launch of the Millennium Development Goals and the preparation of international legislation to prevent violations of women’s rights in armed conflict. But, having seen how diplomacy worked within the UN system, she decided that her “obsession with truth-telling would only get me into trouble in such a furtive world”.

Thanks to a phone number on a restaurant napkin, her path took her to a global network of women activists establishing the “Urgent Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights”.

Her work has ranged across almost all the continents, including North America, Asia, Africa, Latin America, among those living in extreme poverty, in active war zones, and in countries teetering on the edge of civil conflict and widespread famine.

This is not a book about a career. It is about the transformative power of encounter and relationship.

‘What makes you historic?” asks one of the leaders of a room filled with women activists from around the globe, many working against a perpetual backdrop of war. They talk about love, children and families. To her surprise, none of them talks about the groundbreaking work they do. “It was a testament,” she writes, “to their commitment to how women activitsts often work, sharing credit or remaining anonymous, protecting one anothers’ security, and advancing change collectively rather than as individuals.”

When the question is put to Kiri, she murmurs that she is not historic and waves the question on to the woman next to her. At that point the group leader shouts: “Of course you are! Listen to these women around you, really listen to their stories, let them guide you because they have already been you.”

That encounter proved to be one of her powerful mid-course corrections. “Whenever I felt overcome by the vast amount of pain and suffering we were confronting, I would focus on “the love I was creating in my wake, and not just the endless battles that lay ahead.”

Put to the test

Almost as if the pages of her book turned to tracing paper as I read them, I felt I was seeing another text written underneath. It was the words of her teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who had witnessed the devastation of Tibet and its people, crossed the Himalayas with a mission to quell aggression in the world, and had trained her for this.

“The current state of world affairs is a source of concern to all of us,”he said, “widespread poverty and economic instability, social and political chaos, and psychological upheavals of many kinds. The world is in absolute turmoil. We must try to think how we can help this world. If we don’t help, nobody will.”

The title of her book emerges from the intricate tapestry of all she has been through, including her rich love life. When she first falls in love with the tattoo artist she finally marries, she lies on his bed looking through a book of 1920s New York sailor tattoos. She points out that one of them, which proclaims “Fortune Favors the Brave”, is similar to a Buddhist teaching she received.

“We might say ‘Good fortune comes from fearlessness,’ she tells him, “with ‘good fortune’ meaning good karma, and ‘fearlessness’ meaning the courage to overcome fear and defeat conflict. Humans are still evolving, now mentally faster than physically, but we still haven’t figured out how to stop killing and exploiting one another, nor how to peacefully coexist amongst our differences.”

Her words are put to the test in the police convoy that takes her and the other protestors from the notorious Shigatse prison in Tibet, where they have been detained, to the border with Nepal. Sitting next to her in the vehicle is a high ranking officer she termed “The Worst”, a woman who has subjected her to hours of psychotic torment. Kiri summons up her sacred warrior training, bows to her enemy and begins to talk, one human to another.

Even as “The Worst” begins regurgitating nationalistis dogma about the Chinese government having liberated Tibet from the dark ages, tears start to stream down her face. She implores Kiri to come back and visit her, even though she knows her prisoner has been banned from China for life.

“My childhood teachings have, once again, proven true,” says Kiri in the final words of her remarkable memoir, “all conflict is workable, and kindness is always available as a secret weapon for transforming hate. It was my torturer, with her silent tears, who set me free in the end.”

Kiri Westby, Fortune Favors the Brave — An Extraordinary Memoir, Post Hill Press, New York and Nashville, 2020.

ISBN 978-1-64293-343-7; ISBN (eBook) 978-1-64293-344-4

A fuller review of the book is published in The Arrow, “Healing Social and Ecological Rifts – Part 1” July 2021