Sometimes, at the moment of death, a human being becomes immortal. Their spirit triumphs over their mortality. Thus it was this week for the tortured keeper of the treasures of the ancient city of Palmyra.

Three months ago Islamic State fighters overran it.

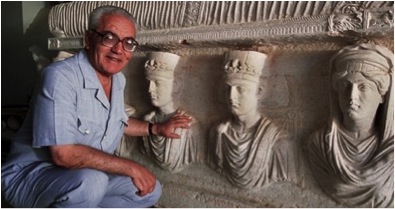

This week, Khalid al-Assad, the 82-year-old archaeologist who was instrumental in the effort to save the site’s priceless antiquities, was publicly beheaded and his headless corpse hung from the remains of a Roman column.

He endured torture for a month, but still refused to disclose where the city’s sacred relics had been hidden.

“His work will live on far beyond the reach of these extremists,” said UNESCO’s Director-General, Irina Bokova. ”They murdered a great man, but they will never silence history.”

Before being seized and tortured by Islamic State, he was urged by fellow archaeologists in the Syrian capital, Damascus, to flee for his life. He is reported to have told them he was born in Palmyra, had devoted his life to the world heritage site and would die there.

Palmyra was once a major link on the Silk Road. Although Islamic State forces have not yet demolished the Roman-era ruins in the city, they have already blown up two of the older shrines in the outskirts. One was the tomb of Mohammed bin Ali, a descendent of Ali bin Abi Taleb, the Prophet Mohammed’s cousin.

These demolitions are the latest of humanity’s centuries-old repositories of scholarship, literature and culture to have been burnt, blown up, bombed and desecrated.

The burning of the royal library of Alexandria (the painting above is from Thomas Cole’s “The Course of Empire”) is often held up as a symbol of the loss of cultural knowledge. Various attacks on it are said to have been ordered by Julius Caesar, Aurelian and the Coptic Pope Theophilius. It is an enduring icon for the deliberate and often systematic destruction of the achievements of civilization.

Sadly, this has recurred so often throughout history that we have a technical term for it: “libricide”, more widely known as “book burning”. In her book Libricide, Rebecca Knuth, quotes Heinrich Heine’s chilling and prophetic words:

Where they have burned books, they will end in burning human beings.

Cultural cleansing

Book burning is only part of it. This onslaught against cultural achievements, establishments and relics is analogous to “ethnic cleansing”. It is part and parcel of humanity’s seemingly endless war against itself.

Archaeologists and cultural historians have a deep understanding of this dark side of our collective history. In many ways, they are the unpublicized heros — like Khalid al-Assad – who do their utmost to stand in the way of this madness.

It’s a madness that spans both history and the globe.

All the palaces and temples of Cusco, the sophisticated capital of the Inca empire, were laid waste in the European conquest of the so-called “New World”. The demolition of the city was part of the human, cultural and ecological devastation visited upon the earth and its peoples from what we now call Alaska all the way to the southern-most tip of Tierra Del Fuego. We are still living with the consequences today.

A year after the demolition of Cusco, Henry VIII ordered the dissolution of the entire monastic system in England. When he unleashed the terror in 1536 there were over 800 monasteries, abbeys, nunneries and friaries. By 1540 there were none left.

One name stands out from that period of conflict and devastation perhaps even more vividly than Henry’s. It is Thomas More, the author of Utopia. He was canonized as a martyr in 1935 and honoured as the “heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians” by Pope John Paul II in 2000. He is famed for his noble and enduring silence, when he refused to support the king’s plan for dominion over the church.

In a chilling echo of this week’s news from Palmyra, Sir Thomas was publicly beheaded — shown in this detail from a painting by Antoine Caron in 1591. His head was then fixed on a pike over London Bridge for a month..

The horrific aftermath

Assaults on cultural sites have become too numerous to list. So much has fallen victim to the eruption of “total war” in the 20th Century and the 159 conflicts around the world, both within and between nations, in the horrific aftermath of the Second World War. Many atrocities have been proclaimed as victories, as Hitler did when he screamed, “The past is in flames!”

We need think only of the “Kristallnacht” in November 1938 when Nazi stormtroopers attacked thousands of Jewish homes and businesses as well as virtually all the country’s synagogues and cemeteries. Prayer books, scrolls, philosophical texts and sacred art were tossed into the fire. It was the prelude to the Holocaust. Heinrich Heine was right.

Three decades later, on the far side of the world, China’s notorious Gang of Four unleashed the Cultural Revolution. Aiming to destroy “the old society”, countless historical relics and artefacts were destroyed. Cultural and religious sites were vandalized and many of them levelled.

Having already been subject to invasion by the People’s Liberation Army in the 1950s, Tibet now faced a further wave of destruction, aimed at wiping out its traditional culture. The combined result, among other things, was the destruction of thousands of monasteries. This is one of Tibet’s most renowned monasteries, Drepung, photographed after the Cultural Revolution.

One of Tibet’s greatest meditation masters, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche – the founder of the contemporary worldwide Shambhala community – wrote about the cultural cleansing that he witnessed before he fled at the end of the 1950s. “Chinese troops broke into the library and threw out all the valuable books, tearing off their covers; the good Tibetan paper was either just strewn around or else was given as fodder to their horses. . . Everything of value in the monastery was removed,” he said.

The immortal spirit

It was the same dark wind of destruction that, in our time, has descended on Palmyra in a different form. Khalid al-Assad withstood it as best he could. That is why he remained firm, silent under torture.

His bravery is eerily reminiscent of the monks at the Tibetan monastery where Chögyam Trungpa was the abbott. In his memoir, Born in Tibet, he describes an elderly lama imprisoned by the Chinese with ten monks inside a small, old chapel used for meditation. They were unable to escape. The lama told his fellow prisoners:

Since this building has been set aside for meditation, it should still be so used, and this experience should make us realize its true purpose. We must accept that what has happened is all part of our training in life. Indeed this is our opportunity to understand the nature of the world and to attain a deeper level. Though we are shut up here as prisoners, our devotions should be the same as if we were freely gathered together in the assembly hall.

That is the last we know of them.

Wherever the spirits of these immortals gather, silent and unbowed, Khalid al-Assad has surely joined them.

25 August 2015