MINDFULNESS INTO ARABIC

One of the leading universities in the Arab world has begun introducing the practice of mindfulness to its faculty, staff and students, and succeeded in developing a ground-breaking translation that expresses the meaning of mindfulness, for the first time, in Arabic. For a rising generation of religious leaders, the building of this bridge between cultures and traditions has deep meaning.

The rising tide of hatred

“It all begins with the idea of ‘them’ and ‘us’,” says the young imam as we sit together on the floor of the mosque talking about the rising tide of hatred in the world. We gather after Friday prayers – young scholars in the rising generation of Muslim leaders – to talk about the global issues now facing humanity.

It is an unusual gathering, because we also practice mindfulness together. “The practice of mindfulness is important,” one of the young imams tells me. “We appreciate it. We have to be fully present in whatever we do. We have to be fully present in our prayers. We have to be fully present with each other.”

Not only is our shared practice of mindfulness unusual, so is our location. We are at Morocco’s leading university Al Akhawayn – often known as AUI – established by royal decree to promote “the values of human solidarity and tolerance” in this predominantly Muslim nation.

This group of about a dozen imams who have completed their memorization and scriptual study of the Quran are now full-time post-graduate students in the university’s comparative religion program. The program was the brain-child of the country’s Minister for Islamic Affairs who wanted this next generation to have a broader international perspective on the diversity of the world’s wisdom traditions.

The university first invited me to present mindfulness practice to the young imams in 2014, to lead an open practice session for the university as a whole, and to give a presidential address on “Seeds of War, Seeds of Peace – Religious Conflict in Today’s World.”

I made no secret of my own buddhist background and took this opportunity to express my deep regret at the rise of buddhist extremism in South and Southeast Asia which has led to devastating attacks on Muslim minorities. The visit also opened the door to an energetic discussion with students and faculty on the question: “Is Enlightened Society Possible?”

We have maintained a relationship ever since, exploring the mindfulness practice tradition together, as well as examining the underlying forces responsible for so much of the conflict and carnage we are witnessing.

Transcending our boundaries

We found that approaching mindfulness practice from the perspective of the ever-growing body of research into neuroscience was particularly helpful and fascinating to all of us. The scientific focus on the physiology and functionality of the human nervous system has offered us the possibility of looking at ourselves and each in other in ways that transcend the barriers of culture, religious tradition, language, and politics.

The deeper we have gone into this together, the more we have come to value our shared humanity as something more powerful and fundamental than our differences. In the midst of the pain, confusion and fear in the world around us, the words of this next generation strike a deep note of understanding, truth and hope.

“Them and us” becomes “them or us”

The idea of “them and us” becomes “them or us” the young imam warns me. “You may be right, I may be right. We both believe we are right. But that doesn’t mean that we cannot make a relationship with each other and work together. We are human beings – which means we are different. We have different backgrounds, different languages, different beliefs. But we are human and it is our humanity that is most important. We are one family. Even now, if you examine our DNA, it is clear. We are one family and that is what is most important.”

Partly because of the bridging function that mindfulness practice can play, and partly because of the considerable interest in mindfulness among business leaders, educators and health professionals, the university’s senior leadership asked to receive intensive “mindful leadership” training. After a presentation to the university’s president and other senior officials, they asked the Cologne-based Kalapa Leadership Academy to provide this training.

The Kalapa Academy has run similar programs for major companies such as Audi, Bosch and Jaguar and for institutions such as Oxford University and the European Space Agency. The academy has just been awarded the “Best Training in Europe” Prize given annually since 1992 for training, consulting and coaching, by the European professional association for trainers, consultants and coaches (BDVT).”

Executive training in mindful leadership

The academy’s founder and managing director, Chris Tamdjidi, and I delivered 10 workshops over a period of two and a half months to Al Akhawayn’s 18-strong Executive Leadership Team. The university was well aware of our Buddhist background in the Shambhala tradition of cultivating enlightened society. It regarded our presence as a contribution to its tradition of encouraging inter-faith dialogue, understanding and mutual learning. While acknowledging this, we nevertheless presented mindfulness practice solely from a scientific and experiential perspective.

The participants in the executive training were given digital Attention Network Tests and psychometric self-assessments at the beginning and end of the training. They received individual profiles of their test results and an aggregated research report on the effects of the training on the group as a whole. The data has been added to the cumulative research findings of the Kalapa Academy.

At the end of the training, in addition to completing the psychometric tests, they talked to us about their experience. They told us they felt the training had made an impact on them in three areas of their lives: individual, professional and social.

“A real change in my life”

“I really feel this has been an experience of such positive energy,” said one, highlighting the individual impact. “I feel physically different. I am becoming more calm,” said another. “I do the body scan before going to sleep, which has made a real change in my life.”

Describing the effect on their professional life, one said, “I am being mindful with my colleagues. We deal better with each other in our meetings and we are more productive.” The training seemed to resonate with the experience many of these leaders had in running the institution’s complexity and diversity. “I now have ‘names’ for the ways of working with others that I knew from my own previous experience,” said one. “I have found the team-building aspect of our mindfulness training to be of great benefit.”

The third aspect that some described the social impact, including on their home lives. “I have learned how to adjust from leaving work to going home,” said one. “I really notice the difference in the ‘me’ I am at home. I am able to close my work day before I leave for home. I now relate to my wife and kids with a far better version of ‘me’ than the previous version of the person who brought the stress of work home with him.”

Progressive possibilities

In the course of the executive training, the former director of the university’s School of Business Adminstration, Dr Wafa El Garah – now Vice-President for Academic Affairs – said they would like to offer a course on “Mindful Leadership” during the business school’s summer semester. Her hope was that this would offer progressive possibilities for mindfulness training to all faculty, staff and students. I have now returned from leading that summer program, daily over seven weeks, including during their observance of the holy month of Ramadan.

“This course was a great opportunity for me to take some time during the day and be with myself,” one of the students said. “It was an opporunity to feel the tension in my body, to feel my breathing, to feel myself actually.”

“Mindfulness helped me a lot,” said another one who, along with the others, made a personal video showing her understanding and personal experience of mindfulness practice. “I’m a person who always finds herself daydreaming and focussing on other stuff – anything but the present moment,” she said. “Mindfulness helped me in being less stressful and in enjoying life.”

Her video shows her teaching mindfulness to her mother and to her younger brother and sister. As one of the other students said, “If we can synchronize the activity of the billions of neurons we have in our brains and nervous systems, what we can accomplish will be amazing.”

“It is our people who suffer most at the hands of ISIS”

After ISIS killers carried out the “Bataclan massacre” in Paris, the university’s young imams sent a message to me asking if I could visit to meditate with them and talk. They continue to be appalled by the staggering levels of violence that are tearing apart so much of the Middle East, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa – and the repercussions around the world. “After all,” as one of them said to me, “it is our people, the Muslims, who are suffering the most at the hands of ISIS.”

“Only violence makes the news, not peace”

“Even worse,” they said, “this death-cult has turned the world against Islam – when in fact what these monsters are doing is against everything that Islam truly represents. We can say this to you from our hearts because we are Islamic scholars and we have trained in this tradition all our lives. But you do not see our voices anywhere in the media, because only violence makes the news, not peace.”

Our perceptions of the world and how these are shaped have been a constant theme in our conversations. Many times the imams have talked about what they believe to be selective interpretation of events by much of the world’s news media.

They point out that a conference held in Morocco earlier this year adopted a Marrakesh Declaration calling for the protection of religious minorities in predominantly Muslim countries. It was attended by some 250 Muslim leaders and scholars from virtually all the main traditions within Islam. I was honoured to be there as part of a small group of international guests from different faith traditions.

The Muslim leaders unanimously agreed “to confront all forms of religious bigotry, villification, and denegration of what people hold sacred, as well as all speech that promotes hatred and bigotry” and affirmed that it is “unconscionable to employ religion for the purpose of aggressing upon the rights of religious minorities in Muslim countries.”

To date, none of us are not aware of any significant coverage of this historic event by any of the world’s major news media.

As a result of the time we spent practicing mindfulness together and having open-hearted conversations, I felt these rising leaders wanted to be offered, not only the hand of friendship, but also a bridge to a world that all too often seems closed to dialogue. They want the walls of ignorance and prejudice to come down. Writing – with their permission – about these intimate exchanges I have had with them is, I hope, a way of bringing their voices to wider attention.

Finding the right word in Arabic

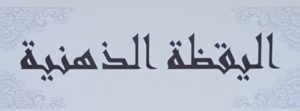

One of the challenges we faced was finding the right word to express the notion of “mindfulness” in Arabic. The original term in the Pali language of South Asia is “sati.”

It denotes the ability of the human mind to be cognizant of its own nature, activity and experience. Dr Jon Kabat-Zinn uses this definition: “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, non judgmentally.” The university’s president, Dr Driss Oauouicha, took the lead in finding a meaningful Arabic equivalent.

“Although you can find translations on the web, there is no translation in Arabic, as far as we know, that really expresses the experience of mindfulness,” he told his leadership team. “Our first efforts were translations based on the French, ‘pleine conscience’. But we felt that was not the full meaning. So we then consulted Professor Bouchaib Idrissi Bouyahiaoui, the founding director of Morocco’s national translation and interpretation school. We discussed it together for some time and I think we came up with an expression that seemed to both of us to convey what we are talking about. In French this would be ‘la veille de l’esprit’, or in English, ‘the mind fully awake and observing’.”

A phonetic rendering of the term in English would be: “Yah-khah-dha Dhih-ní-a”.

Soon after this translation was adopted by the university, we were able to present it to Her Excellency Ms Ohood Al Roumi, the recently appointed Minister of State for Happiness of the United Arab Emirates. She was visiting the London School of Economics in June this year to examine its research into happiness and also requested meetings with the University of Oxford Mindfulness Centre and with the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Mindfulness and the UK Mindfulness Initiative. They made a considerable impact internationally with the publication of their 2015 report, Mindful Nation UK.

The delegation that met her included Chris Tamdjidi as well as the founder of the UK parliamentary group, Chris Ruane, who is shown above presenting the framed translation. During the meeting, Minister Al Roumi explained that she herself had already engaged in a mindfulness course and that both she and a number of her colleagues who took part found it to be extremely helpful.

“Absolutely, this is it!”

Minister Al Roumi remarked that there was no word for mindfulness in Arabic, and there needed to be one. However as soon as she saw the framed calligraphy she exclaimed, “I agree, absolutely, this is it!”

The students and faculty in Morocco were inspired at news of this endorsement and by the feeling that these initiaives could spread throughout their region. “This could have a really positive impact on the culture in our region and how we communicate and work together,” said one.

“I really hope we can show the world how mindfulness works,” said the young woman who is getting her family to practice with her. “And I really hope that we can make Morocco a leader in mindfulness.”