International legislators gather in London to contemplate mindfulness in politics

“I got thrown out of yoga for laughing,” UK government minister Tracey Couch told an international conference of legislators exloring mindfulness and public policy. “So mindfulness as a means of helping me deal with my depression and anxiety was not something I thought was going to work.”

As Minister for Sport and Civil Society and a Conservative member of parliament, she was opening the first-ever international gathering of political leaders, educators, scientists, researchers and medical specialists to discuss “mindfulness in politics”. The event in London’s Westminster was attended by legislators from 15 nations, invited by the nation’s All-Party Parliamentary Group on Mindfulness.

‘It really clicked”

“After attending my third session of training offered by the Mindfulness Group, I got it,” she said. “It really clicked. This is helping me: the understanding of who you are and how you can cope. Mindfulness teaches you to be in the present moment and not to be beating yourself up.”

Personal as her statement was, it was the opening of an event focused on public policy. “In fact,” said Dr Jon Kabat-Zinn, the molecular biologist described as the godfather of the contemporary mindfulness movement, “I always saw my work as a public health intervention.”

In 1979 Dr Kabat-Zinn founded the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, and in 1995, opened the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society. “When we started, there were no grants for mindfulness,” he told the conference. “Now there are scores of millions of dollars going into mindfulness research every year.”

“What we are learning from neuroscience now is that the brain is an organ of experience,” he said. “It is actually shape shifting, transforming itself on the basis of our experience from moment to moment. This is called functional connectivity or neuroplasticity. It’s been shown that in eight weeks of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction different regions of the brain get more dense. Other parts, like the amygdala which is the stress reactivity centre, actually reduce.”

The impact of the MBSR training on people suffering with depression was a key factor in bringing mindfulness to the attention of the British Parliament. Chris Ruane, Labour MP for the Welsh constituency of Clywd, broke the ground with an intervention in the House of Commons in 2012.

He presented research findings on the benefits of mindfulness training for people suffering from depression and dependency on prescription drugs. He called on the government to explore the application of mindfulness in health care and other public services, including those offering support to the unemployed.

Mindful Nation UK

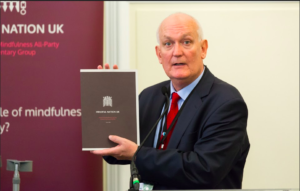

In the five years since Chris Ruane’s speech, the research has continued. With the formation of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Mindfulness – and painstaking training of more than a hundred MPs, lords and civil servants – came the publication in 2015 of the group’s own research report Mindful Nation UK.

The parliamentarians’ report made policy recommendations for the practical application of mindfulness training in the areas of health care, education, the criminal justice system and the workplace.

At the London conference, an expert panel presented the results of efforts to implement the report’s recommendations. Hearing the results was one of the features that drew more than a hundred leaders and professionals in the fields of mindfulness and politics from around the world to the event. They came from countries as diverse as France and Sri Lanka, Croatia and Israel, the United States and Morocco.

“One billion people will suffer from depression at some point in their lifetime,” Willem Kuyken, Professor of Clinical Psychology and Director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, told the gathering. “The priority for health care systems around the world is going to be moving away from communicable diseases, dysentery and water-borne diseases to mental health. That’s a massive challenge we all face.”

A growing body of clinical research

There is a growing body of clinical research and practice that strongly suggests mindfulness training could be a key component in meeting that challenge. Dr Rebecca Crane, Director of the Centre for Mindfulness Research and Practice at Bangor University, Wales, described the development of a further mindfulness training system known as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). Integrating mindfulness with cognitive science, it is particularly designed for the needs of those suffering from depression.

“We are still in the midst of the research,” she said. “In trials, MBCT halved the expected rate of relapse. There is increasing vulnerability with each episode of depression, and MBCT really supports people to reduce that vulnerability.” After further trials in 2004, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), recommended its use in the country’s National Health Service (NHS).”

Within only two years of the publication of the Mindful Nation UK report, two of its four recommendations for health policy are now being implemented. MBCT has become a “mandated” primary care intervention for psychological therapy services across England. This endorsement requires that it become widely available. The second policy success is that the NHS has agreed to fund the training of MBCT teachers for psychological therapy services. The teacher training will start in March 2018.

The impact of trauma and abuse

The Mindful Nation UK report also recommended that the NHS and the National Offender Management Service should work together to ensure the urgent implementation of NICE’s recommended Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) for recurrent depression in the country’s prisons and parole system.

“The majority of people with whom we work face significant challenges, environmentally, psychologically and in relation to the impact that trauma and abuse have had on their personality formation,” said Amaladipa Remigio, Head of Public Protection for the National Probation Service in Wales. “This can result in behaviours that are harmful to themselves, to others and to society.”

“Levels of addiction and poor mental health are much higher than in the rest of the population, and incidents of violence, suicide and intentional self-injury have been at their highest recorded levels in the last 12 months. Recently, an offender was taking their own life every three days in British prisons,” she said to audible gasps from the conference.

In an attempt to find out if mindfulness training could be helpful, her service ran three experimental programs in high-risk offender hostels in Cardiff and Swansea, followed by a much larger research project designed in conjunction with Swansea University. It involved both offenders and probation officers and was conducted between January and October this year. “Mindfulness training is reducing stress levels, improving emotional self-management, creating a psychological space where more creative responses can develop and enhancing resilience, creativity and compassion,” Ms Remigio said.

“I’ve spent 24 out of the last 30 years in prison,” said Mark, a former offender released within the last year. He held the conference spellbound as he described his journey and his incessant mental turmoil. He described how, after attending his first mindfulness session, he went home, “did a short practice” before lying down on his bed and slept for what he said was the first time in those 30 years.

“Mindfulness has given me my life back,” he said. “I can walk down the street. I can stand here today. Believe me, for me this is a big, big deal. For a stubborn person like myself, if it can do it for me, then there’s an awful lot of other people in prisons today that could benefit from this.”

It is not only those who are incarcerated or on probation who are affected. Nicola, a probation officer, reported on the postive impact of mindfulness practice in what she called her “relentless” work, and Baroness Angela Harris spoke of the successful efforts to introduce mindfulness therapy into the units where British police receive trauma counselling and care.

Reflecting on the research data and testimonials, Dr Kabat-Zinn told the gathering, “I don’t think we realize the extent to which we are miraculous beings. Humans have this profound capacity for imagination, creativity and kindness even under very, very difficult circumstances.”

“Are you proposing an anti-politics?”

“Mindfulness is about how we carry ourselves,” said Kabat-Zinn. “Carrying is the root meaning of the verb ‘to suffer’. We are carrying a lot of negativity, often a lot of anger and resentment. It weighs on us. But what if we learned how to carry things with a greater embrace of awareness? Yes, the circumstances outwardly would be the same as they always were, but inwardly we would have potentially new degrees of freedom in working with old and very, very knotty problems. We can modulate our behaviour. We can learn.”

“I wonder if you are proposing an anti-politics,” asked Alan Howarth, a Labour peer in the House of Lords, drawing a sustained round of applause. “During my political lifetime the dominant political ideologies have been about conflict and competition. Does this offer an antidote to the ideologies of conflict and competition? Or are you suggesting that politics is capable of being made humane?”

“Is the world, as we have constructed it, up to the task?” Kabat-Zinn asked in response. “It is getting more urgent to know the answer to that question. We are really talking about an orthogonal rotation in consciousness. The word means ‘rotated at ninety degrees’. Instead of running on auto-pilot until we are at each others’ throats, can we see with fresh eyes so that we are not using our science to destroy more and more people?”

“Maybe it starts with talking to people we don’t usually talk to. Mostly we are in an echo-chamber,” Kabat-Zinn replied. “We need to train ourselves in listening, so we become a stethoscope listening to the heart of the country.”

[The international conference, hosted by The Mindfulness Initiative, was held in London, October 2017.]