The opening words of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are as true today – and as urgently needed – as they were when they were adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948: “Recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

The same can be said for Amnesty International, the global people’s movement for human rights. It now has more than ten million people in 150 countries. The challenge it faces today is as great as it has ever been.

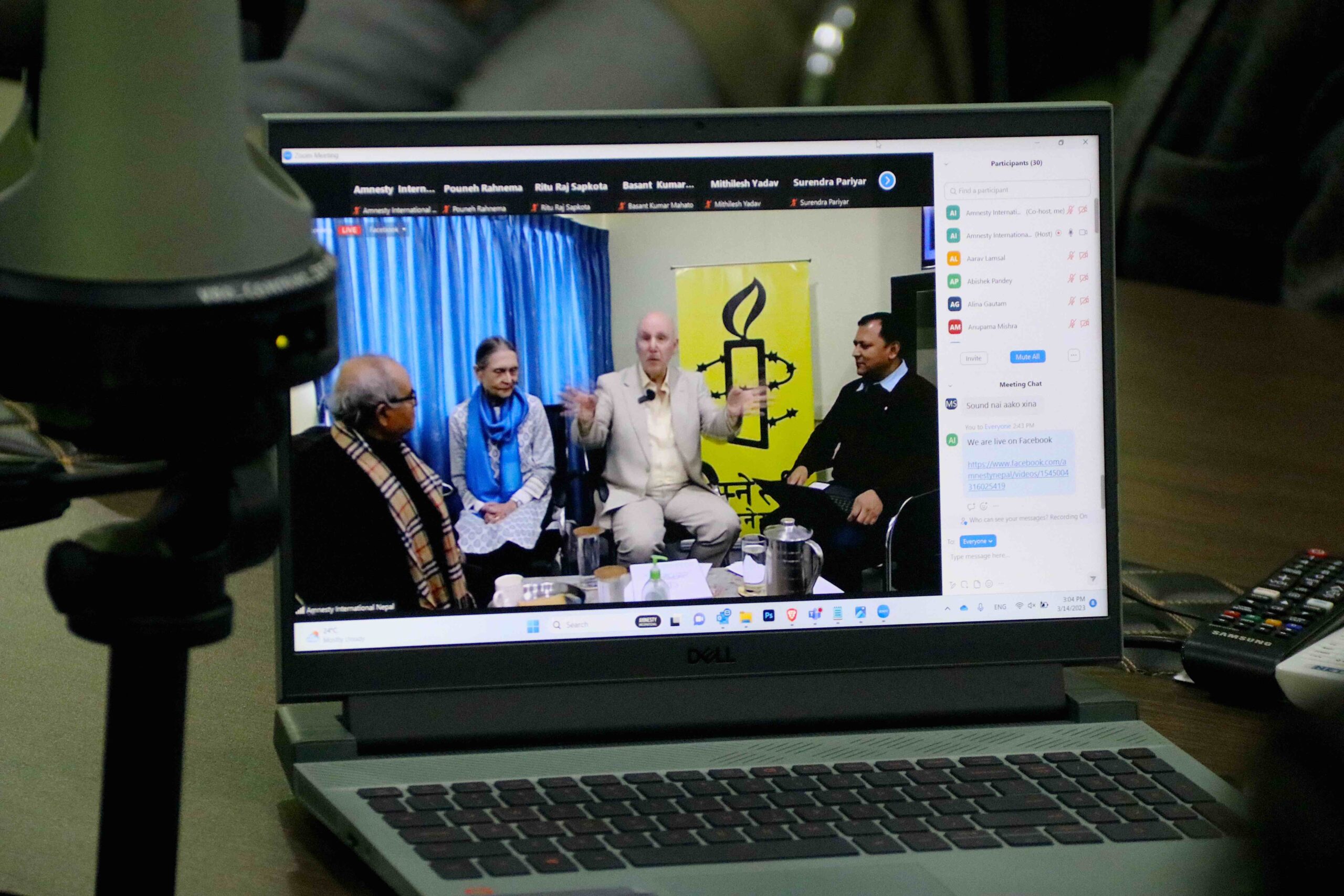

These were the recurring themes of a Himalayan gathering (pictured above) that took place in early March 2023 at the headquarters of Amnesty International Nepal – a nationwide network of more than 7,000 activists right across the country’s provinces. The gathering was convened by and presided over by Amnesty International Nepal’s current dynamic director, Nirajan Thapaliya.

Amnesty International Nepal has made the recording of the full event, which includes a discussion of the challenges facing the country now, available here.

Universality and non-discrimination

Universality and non-discrimination were key themes in the meeting. The gathering was convened to examine some long-standing issues in the development of Amnesty International in countries like Nepal and to assess the challenges being faced by human rights activists around the world at the present time.

It is sometimes argued that the idea of “human rights” is a western concept. In fact, the drafting of the Universal Declaration was a deliberately international, cross-cultural project from the beginning. It involved people from all continents, different cultures and political systems. The extensive international consultation included eminent figures such as Mahatma Gandhi.

Two South Asian women played a key role. Hansa Mehta of India was widely credited with changing the phrase “all men are born free and equal” to “all human beings are born free and equal”. Lakshmi Menon, who later became the chair of Amnesty International in India, argued for the principle of non-discrimination. She succeeded in getting the phrase “the equal rights of men and women” into the preamble and the “universality” of rights respected in in the declaration as a whole.

Examining the past, assessing the future

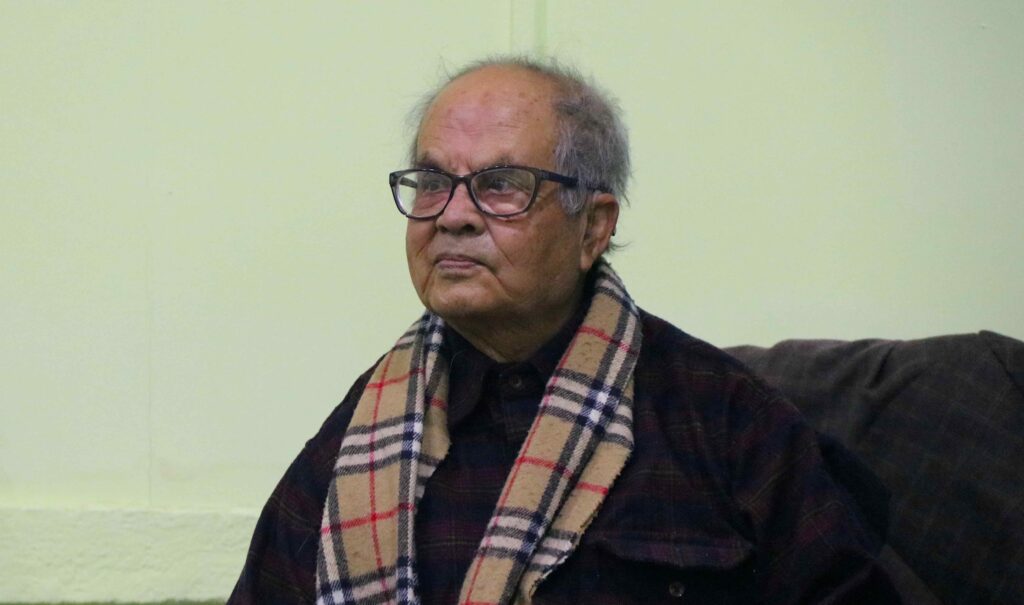

A special feature of the gathering was the presence of the founder of Amnesty International Nepal, Nutan Thapaliya. He is seen here greeting Richard on his arrival at the Amnesty International headquarters in Kathmandu.

Now 94 years of age, Nutan was the lawyer who was instrumental in establishing the organization in Nepal in 1969. He worked closely with Richard who, in the early 1970s, was the organization’s Field Secretary in Asia. Also present at the welcoming, and seen in the photo, was Dhruba Kumar Karki, former Chairperson of Amnesty International Nepal (2006-2008).

It was an opportunity to look backward to an eventful past when Amnesty International Nepal was just getting underway and to look forward to new developments and threats in today’s world.

The entire event was a hybrid in-person and on-line gathering, with people joining not only from different regions in Nepal, but also from countries ranging from the UK and Denmark to Iran.

South Asian voices for human rights

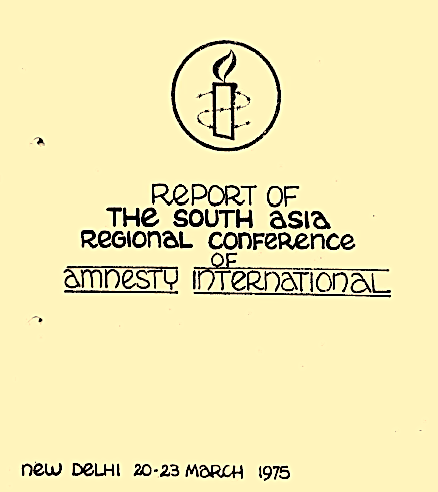

Of particular interest was the opportunity to review the original report of the South Asia Regional Conference of Amnesty International, held in New Delhi, 20 -23 March 1975. The conference, which was jointly convened by Amnesty International leaders in South Asia, was attended by four delegates from Nepal, eight from India (including Lakshmi Menon), four from Bangladesh, three from Pakistan, and two from Sri Lanka, as well as the Chair of Amnesty’s International Executive Committee and the organization’s Secretary General.

“This was a historic conference,“ said Director Nirajan Thapaliya, “the first of its kind in South Asia. I was still not born then! But we will carry on in this spirit. We will carry the flame!”

The report pointed out that, in the countries of the region, “the common features of wide- spread poverty, hunger, disease, unemployment, illiteracy and inadequate communication facilities tend to result in political conditions where few or no fundamental freedoms are guaranteed and where organizations which are or appear to be politically active may be banned or at risk.”

“In this context,” it said, “Amnesty International must concern itself with the long-range need to cultivate respect for human rights and to awaken people to the possibilities and the need to protect and defend victims of human rights violations.”

The delegates called for a different organizational model: working through networks and cooperating with other effective organizations. Richard pointed out that this is exactly what Amnesty International Nepal is doing, such as with its recent Social Justice conference. “There is tremendous strength and outreach in this collaborative approach,’ he said.

The conference delegates stressed the importance of Human Rights Education at all levels of society. “In the face of repression and brutality people think that is the norm – because that is what they have been subjected to all their lives, for generations. Instead they need to understand that human rights are the birthright of every single human being.”

There was a recognition of the need to move beyond being an English-speaking elite. Much more material needed to be translated into local languages, said the delegates. An information hub was needed in the region itself. So the first outpost of Amnesty International outside Europe – the South Asia Publications Service – was established in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Courage, determination and discernment

Working for human rights anywhere in the world takes courage, determination and discernment. “This is the spirit we have to have,” Richard told the participants. “We can have all kinds of troubles. It is not a question of whether we succeed today or fail today. What matters is that we have a serious vision of how society – our human family – takes the next step in its journey to begin expressing and implementing the vision of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

“This is not easy work,” he said. “It is the work of generations. Things go up and down, but we need to be very clear about the goal.”

The brave founders of Amnesty International Nepal faced many challenges more than 50 years ago. Richard spoke fondly of his work with Nutan Thapaliya and described how they would go together to Kathmandu Central Jail. “Thanks to his standing as a lawyer,” Richard said, “Nutan would be able to get the guards to bring the political prisoners to the barred gateway of the prison to meet me.” He said it was thanks to Nutan and all the courageous lawyers and other human rights defenders in the country that they were able to assemble, painstakingly, possibly the most comprehensive details on the hundreds of political prisoners held in the country at that time, and get it out of the country to Amnesty’s International Secretariat in London.

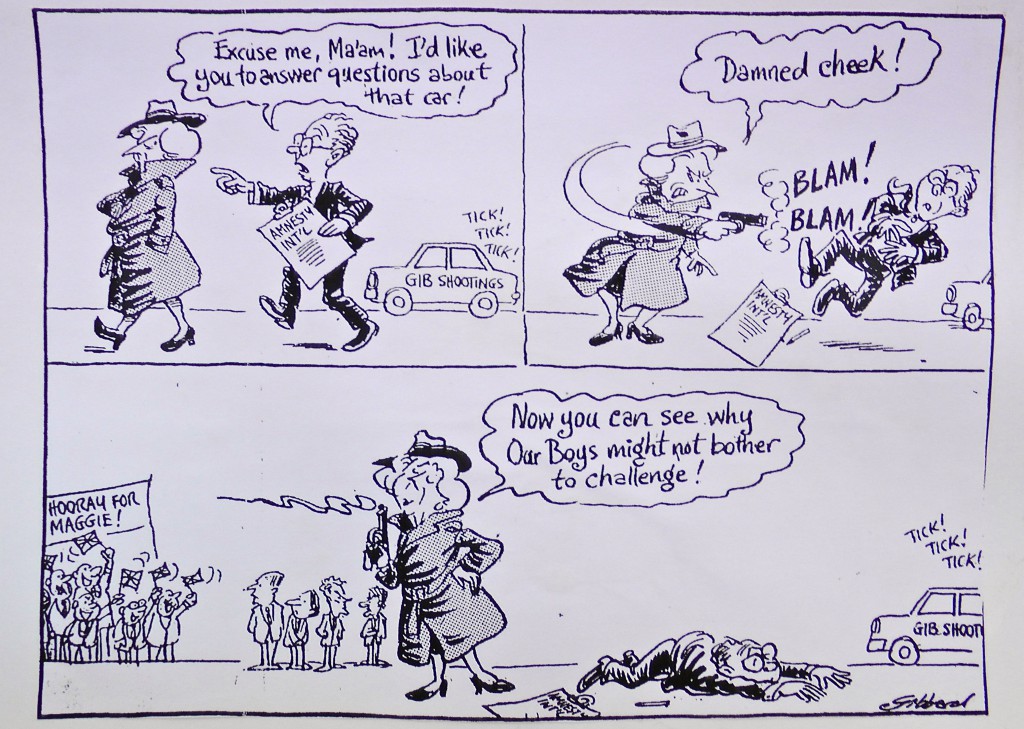

Shot dead by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

The meeting was surprised when the director of Amnesty International Nepal, Nirajan Thapaliya, called up on the screen this cartoon of Richard being personally assassinated by the Prime Minister at the time, Margaret Thatcher. She was often referred to as “The Iron Lady”.

Richard gave a vivid description of facing hostile questions when Amnesty challenged the British government over the fatal shooting of the three suspects claimed to be planning a bomb attack. The confrontation with the British Government showed that the work of Amnesty International applies to countries and governments in all parts of the world. He said the movement must be willing to stand up for human rights wherever they are violated and face the wrath of those in power.

Amnesty International made headlines in South Asia in March with the release of its annual review of human rights worldwide. “As South Asia sits on the brink of a volatile and unpredictable future, it is important now, more than ever, to keep rights squarely in the centre of all negotiations and conversations,” said Senior Director of Amnesty International, Deprose Muchena, at a launch of the report in Colombo, Sri Lanka – as reported by the independent Groundviews – journalism for citizens.

This perspective came up early on in our “Himalayan Gathering”. Nepal, like so many countries that have emerged from years of war, faces the two-fold challenge of establishing truth and justice for atrocities that happened in the past as well as getting their current governments to act in accordance with the law, the constitution and the promises they have made. These are two of the overarching aspects of the complex human rights dynamic that Nepal faces. This is also true for much of South Asia as a whole, and we also see this pattern in countries worldwide who are dealing with the issues of truth, transitional justice, reconciliation and peace.

The rising generation

A lively question and answer session followed with the many participants who had filled the meeting space in the Kathmandu Amnesty headquarters. They included many members of the rising generation who are thoughtful, inquiring and committed to addressing the many human rights issues in their society. You get a feel for the dynamism of the movement in Nepal and also its increasingly inclusive membership from its website.

A month after our gathering Amnesty International Nepal held its Youth Mela in Besisahar, Lamjung. The theme was ‘Building Bridges, Breaking Barriers: Youths in Action’. The three-day festival focused on facilitating interactive programs centered on significant human rights issues for AI Nepal’s youth members. For the discussion we had during our gathering in March on current issues in Nepal and other challenges being faced by the movement internationally, please view the recording by clicking here.

Richard was accompanied by his wife, Jane Ward, who had also been in Nepal with him in the 1970s. Jane worked for many years in the Office of the Secretary General of Amnesty International with particular responsibility for organizing the International Council Meeting, the movement’s supreme governing body. At the end of the session, both she and Richard were presented with gifts from Amnesty International Nepal – a beautiful silk shawl for Jane and a traditional Dhaka Topi, the distinctive Nepali cap, for Richard. Expressing his thanks and appreciation for everyone, he said, “I feel you have made me an honorary citizen of Nepal!”